Mid-nineteenth century North America was fascinated with the idea of communicating with the dead. The doctrines of Spiritualism, which stated that the dead could communicate with the living, had captured the imagination of war-torn nations in South America and Europe, and in 1848 found fertile soil in Hydesville, New York. It was there that the Fox sisters, Kate and Margaret, claimed to communicate with the dead, amazing folk who heard seemingly unearthly rapping sounds responding to the questions posed by the girls (later in life, in 1888, the sisters confessed that they had faked the sounds by cracking their toe joints, although a year later Margaret recanted her confession claiming it had been made under duress). Their table rapping inspired a culture struggling from the casualties of Civil War, at a time when then average life span was 50 years, and Spiritualism grew in popularity throughout the latter nineteenth century. This was also a time for great inventions, such as the telegraph and telephone which permitted communication from great distances. It was not hard to imagine that other innovations, such as the Ouija board, might allow for communication between the deceased and the living.

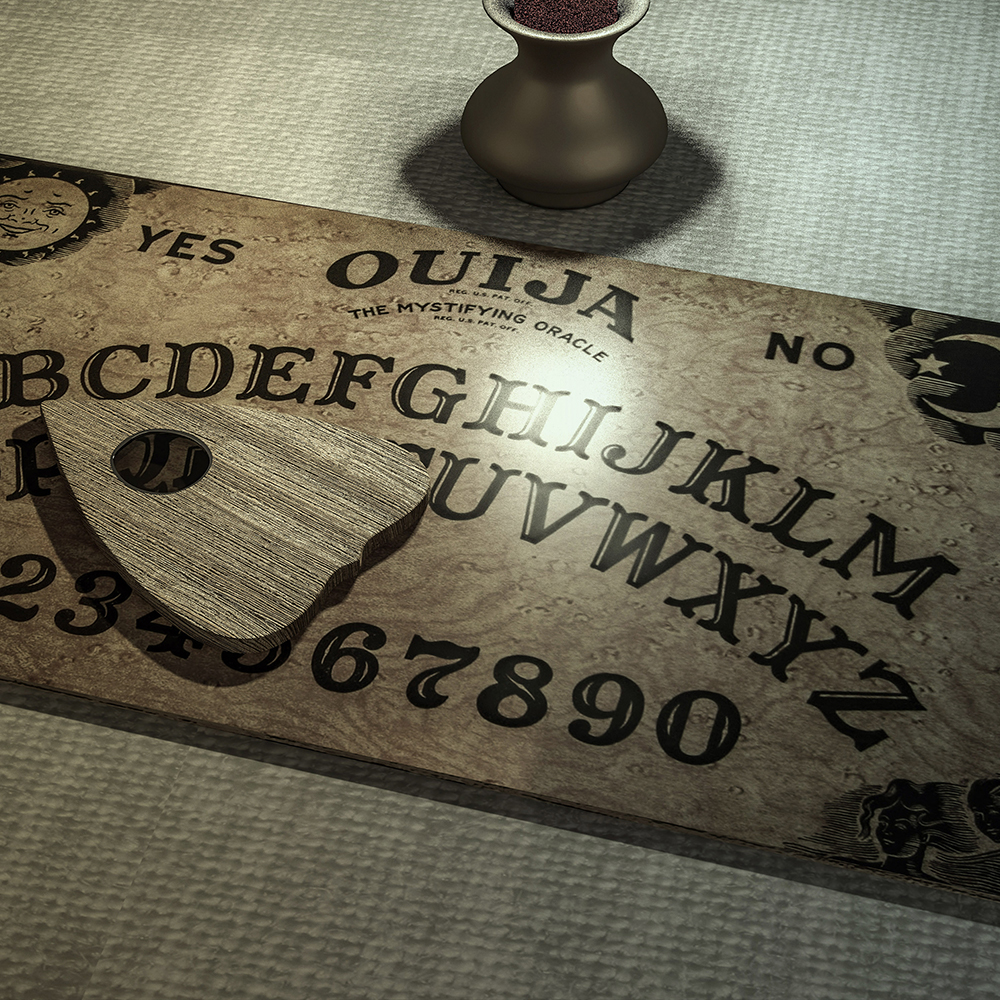

Spirit communication was at first cumbersome, as it relied on someone announcing the letters of the alphabet while others engaged in table tipping, whereby the rapping of the table leg chose letter after letter. Improvement came in the form of a planchette, a heart shaped plank of wood supported by two rear casters and a pencil at its narrow end. The scribbling of the planchette was sometimes indecipherable, but this device lead to the idea of the planchette serving as a pointer. Various alphanumeric platforms were developed, such as printed disks that turned in relation a fixed pointer. Not until 1886 do we first read a description resembling the Ouija we now recognize, for which the pointer–still referred to as a planchette–moves independently across a board.

It was in 1890 that the Ouija board we all know today was commercialized by the Kennard Novelty Company, named after Charles Kennard, with the help of several investors, including Elijah Bond and William Fuld, all of whom at various times claimed to have been the original inventor, although talking boards such as the Ouija had been known among Spiritualists for several years prior to their involvement.

There are some good stories about how the name Ouija came to be, the most popular being that it was spelled out by the planchette when Kennard and Bond’s sister-in-law Helen Peters asked what this new device ought to be called. Kennard believed Ouija to mean “good luck.” Years later, William Fuld, who took over production of the Ouija board, claimed that the name meant “yes, yes,” combined from the French word Oui and German Ja, a legend that still sticks today.

Another popular story claims that the Ouija was approved for its patent only after Elijah Bond and his sister-in-law Helen Peters impressed the patent officer, whose name was allegedly unknown to them, by using the Ouija to reveal his name.

For an instrument as focused on language as the Ouija, it is little wonder that its own proper name must be stressed. While all manner of alphabet boards are commonly referred to by the name Ouija, the word itself is currently trademarked by Hasbro, Inc. Similar products are better referred to as talking boards.

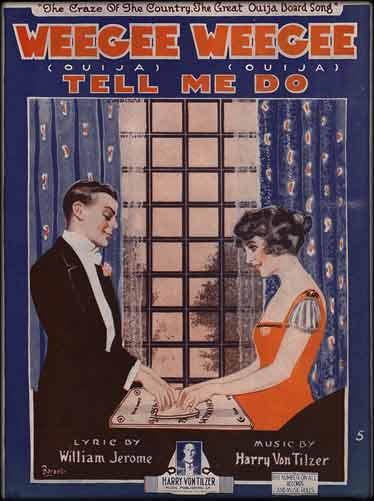

By the beginning of the 20th century the Ouija board had become a cultural phenomenon. It appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in an illustration by Norman Rockwell in 1920, the same year that a popular bit of sheet music titled Weegee, Weegee, Tell Me Do circulated. I won’t torture any of you by having me sing it, but some of its lyrics include the following:

There is a game played by nearly every family

seems to be the thing

Rich folks and poor folks play this little game

to see what future days may bring

From just these few verses we learn just how common and mainstream the Ouija was, with nearly every family playing with one. Rich folks, poor folks, it spanned class definitions, which makes sense given that it was inexpensive, and widely available. Folk played this little game to see what future days may bring, meaning it was used as a form of divination, of fortune telling. The song goes on to tell us how it was used by young and old, during daytime and night (although other accounts suggest that it was most commonly an evening endeavor, taking place following dinner and chores). So, this song, which corresponds with many other accounts, tells us much about how well adored the Ouija was, at least during this time period of the 1920’s.

Though it waxed and waned in popularity, its presence remained consistent, with renewed interest occurring after each world war, when just as they had in the civil war, folk turned to the Ouija to contact those whose lives had been lost.

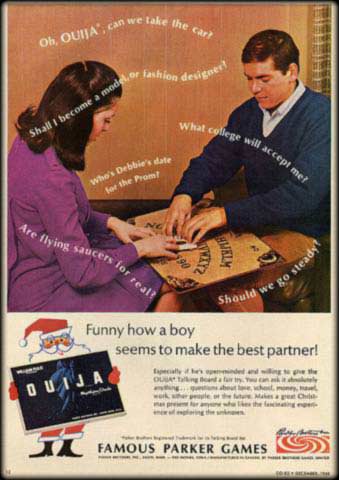

For much of its history in the mid 20th century, the Ouija was considered a fun throwback game, often mechanized beside other popular board games like Monopoly. It retained an air of mysticism, but a less serious one. Much of the culture at that time represented witchcraft and devils in playful ways… consider Samantha Stevens’ use of the Ouija board on the tv show Bewitched. This innocent perception would change, however, turning the wholesome Ouija into a tool of the Devil in the minds of many Americans.

This change in attitude happened in the early 1970’s. This was a time when many people, especially young hippies, began exploring Eastern magical traditions and the occult in a big way. It was also a very tumultuous time, which some blamed on occult influences. The movie The Exorcist, which came out in 1973, tapped into this fear, with the protagonist, young Regan, played with a Ouija board, which the film suggests served as a gateway to her being possessed by the devil. This backlash against hippies and the occult ran its course, however the reputation of the Ouija as a dangerous tool of Satan persisted. This is an important part of its history, this switch from parlor activity, into a satanic portal allowing demons to escape hell and torment slumber parties.

This reputation affects its use. If you are afraid of using a Ouija board, chances are your experience will be affected by that fear. This is part of the reason why I tend not to emphasize its spooky reputation, but rather focus on how common and almost mundane the Ouija was for close to a century, before our occult fearing society engaged Hollywood in making it synonymous with demonic possession. Given its popularity in horror movies, this sinister theme will likely be with us for a while. But I’d like to encourage everyone to remember that this was not always the case, and that this campaign of fear is reason why so many claim to have had negative experiences with it.

In the early 21st century there was a renaissance for talking boards. No longer was the production of such items limited to novelty companies alone. In the early 2000’s personal printers had evolved that were able to product colorful images on A3 paper (13”x19”). This allowed individual artist and small cottage businesses to produce their own designs. Online marketplaces such as Ebay and Etsy allowed traditional wholesale arrangements to be bypassed. This is where I came in, creating Carnivalia in 2004 and producing a line of talking boards. In the following decade, laser technology would allow many small producers like myself to create designs etched in wood. As technology improves and becomes more accessible, I have no doubt that those of us who love creating talking boards will discover new ways to create innovative designs.

The Ouija board remains an iconic fixture in North American culture. We may at times bemoan its negative reputation as risky portal to Hell and the mouthpiece of demons, however what we have gained is a shared rite of passage, for many of us recall being spooked as the planchette seemed to move on its own.

©2018, Chas Bogan